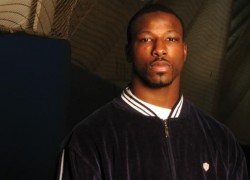

Jason Avant is pissed off. He’s an All-American, so why is he sitting on the bench he thinks? No. 9 Washington is on the opposite sideline, and he should be taking apart their secondary. Sure, he ran out and touched the banner in front of the 111,000-plus crowd, but if he’s not playing, it doesn’t matter.

He spends the first quarter glued to the bench, grumbling to himself about the injustice that has been done to him. He looks around for fellow freshman receiver Steve Breaston, who knows what Avant’s going through. But Breaston’s not sitting on the bench, he’s up on the sideline, yelling and cheering. This freshman is being redshirted — he can’t play this entire year — and he’s the one excited?

Avant’s not going to be the one complaining while his friend is fired up, so he rises and joins Breaston. It all begins to soak in: the crowd, the tradition and his teammates laying it all on the line. He begins to cheer, pulling for his teammates in a tight game. When Phillip Brabbs hits a 44-yard field goal as time expires, Avant runs on the field in jubilation with the rest of his teammates.

“I understood what being a Michigan Man was all about,” Avant said in an interview with the Daily. “It wasn’t about my talent anymore, it wasn’t about me being the best football player, but me encouraging my university, me encouraging my teammates, and that was the change in my career.“

****

It’s a Sunday, so Avant is going with his Granny to church. Not that he has much of a choice, lest he face the wrath of her bible and belt. Lillie Avant, known as Granny to the rest of the neighborhood, raised Avant his entire life. His mother dropped him as a baby and never came back. His father, Jerry Avant, was in and out of prison. A stern woman with a strong faith, Granny raised her grandson as if he were her son.

Their neighborhood was the Altgeld Gardens Projects on the South Side of Chicago, a place most famous for its asbestos. There were drugs and opportunities to go down the wrong path, but Granny’s faith kept Avant on the right side of the tracks, praying for him every time he went out.

Like most kids growing up in the Windy City in the era of Jordan’s Bulls, Avant’s game was basketball. And a baller he was, beating older guys on the playground, taking their money and pride in the process. It wasn’t until his sophomore year at Carver High School that he became a football player.

Carver was short on athletes and funds, so Avant’s basketball coach — who held the same position with the football team — made an ultimatum: if you want to play basketball, you’re going to have to play football.

Avant’s football career got off to an inauspicious start. After one day of the fullback repeatedly popping him, he quit. He didn’t want to get hit. But Granny wasn’t about to let Avant give up after one day. She convinced him to go back out with the squad. With his position switched to running back, Avant started to like the game a little bit more.

In his junior year, Avant switched positions again, this time to wide receiver. And quite the receiver he was, setting school records in receptions, receiving yards and touchdowns. Within two years of first playing football, Avant was an High School All-American.

New to the game of football, Avant wasn’t exactly well-versed in the recruiting and rah-rah tradition of college football. But he knew of this program with history, Michigan, and he remembered Charles Woodson smiling with a rose in his mouth. His interest was piqued, so he began to look into the program. Its winning ways and high academic profile only furthered his admiration. When Lloyd Carr came calling, Avant couldn’t resist signing with the national championship-winning coach.

“I thought Coach Carr was genuine,” Avant said. “I thought he was tough and I thought he went out of his way to come out to the projects, where most of the coaches were scared to come and visit me.”

****

After a freshman year dedicated to getting stronger and faster, Avant entered his sophomore year looking to emerge a star after having only two catches in his Michigan career. But that stardom wasn’t going to come any time soon, as Braylon Edwards had emerged as the leading man of the receiving crew after a 1,035-yard, ten-touchdown season. Anyone who had known Avant as a hot-headed All-American a year before would have expected sullen response to the thought of playing second fiddle. But two events in Avant’s freshman year changed his mindset: the Washington game and the reemergence of his faith.

At the end of his first year at Michigan, Avant submitted himself wholly to Christ. His outlook had changed.

“It was no longer about going out and catching ten passes a game, me being this and me being that, and trying to do it on my own,” Avant says. “My mindset was, ‘Lord, whatever you give me, I’ll be satisfied. I just want to play my hardest so when people look at me, they’ll see you playing.’ ”

No more complaining to quarterback John Navarre about not getting enough passes, because Avant understood now what his playing meant. He was not only playing for God, he was playing for all those who didn’t get out of the Garden Projects, those in the drug game, locked up or dead from the fast life. He practiced what his receivers coach Erik Campbell preached: ‘Never count catches. Only count wins.’

In an era of big-ego wide receivers, Avant was the ultimate team player, quietly gaining a combined 1219 receiving yards and five touchdowns in his sophomore and junior years, while earning a reputation as a thunderous blocker. But when Edwards graduated to the NFL at the end of Avant’s junior year, it was time for the team player to become a team leader.

“My senior year was really hectic for me,” Avant said. “Here I was, used to having a security blanket in Braylon, with him receiving all the attention, allowing me to have one-on-one coverage. Now I’m the guy who’s being doubled, the guy who is the key focus of the defense as Braylon was.”

Avant’s senior year was bittersweet. On a personal level, it was a fantastic year, as he racked up 82 catches, 1,007 receiving yards and eight touchdowns. But on the team level it was a tough year, as Michigan struggled to a 7-5 record after beginning the season with national championship dreams. Avant’s four years of selfless play did not go unnoticed though, as he won the prestigious Bo Schembechler Award, given to Michigan’s most valuable player.

“When I think about it, I can almost cry,” Avant said. “Not because the award meant that much, but that Jesus Christ helped lead me from a terrible situation that I was in to graduate from Michigan. Winning the Bo Schembechler Award, the most prestigious award for an athlete in our school, to see some of the guys on the trophy list, it was just a humbling experience.”

****

Coming off a 1,000-yard season at Michigan, one would have expected Avant’s stock among NFL scouts to be sky-high. But the NFL Draft process was a difficult one for him. While Avant’s talents were obvious on tape, his measurables didn’t scream high draft pick. A 4.73 40-yard dash time caused him to fall to the fourth round of the 2006 NFL Draft, where the Philadelphia Eagles snatched him up.

Thankful for being drafted, but angry for seeing receivers he felt worse than him drafted ahead, Avant looked at his fourth-round selection as an opportunity. He could prove himself as an underdog, that with hard work and faith, anything is possible.

His rookie season was spent working relentlessly to make a talented Eagles team coming off a Super Bowl appearance. Training camp went without getting that dreaded call to drop off his playbook, but earning a roster spot didn’t satisfy him. After a run of wide receivers who steered away from contact, Avant endeared himself to both the coaching staff and Eagles fans by showing no fear in going across the middle to catch passes. His blue-collar style both on and off the field made him a Philly favorite.

After seeing no playing time throughout much of his rookie season, Avant finally opened up eyes after getting his first TD on New Years Eve against the Falcons. His patience paid off, as he entered his second season as a key slot receiver in the Eagles’ pass-heavy offense. His star has been steadily on the rise since, going from 23 catches in 2007-08 to 32 catches in 2008-09 to 41 catches last season. Along with two talented young receivers in DeSean Jackson and Jeremy Maclin, Avant has emerged as part of one of the most feared trios in the NFL, acting as a mentor to the phenoms.

Still playing off of his smaller-than-expected fourth round rookie salary, the Eagles rewarded Avant with a new five-year contract extension. Never one to overtly show his wealth, Avant was happy not only for the security given to him and his wife, Stacy, but the ability to give back through the social work he does with his church. Never forgetting his own rough upbringing, Avant is constantly looking to help give at-risk youth an opportunity to succeed.

*****

It’s 4:15 p.m. in Philadelphia. The Eagles are facing the Packers to open the season. With a new contract in tow and role as the Eagles’ go-to receiver on third down, things have never been more settled for the man from the Altgeld Projects. Still, the nerves from running out onto Lincoln Financial Field in front of 67,000 screaming fans remains. He tells himself a prayer he says every game:

“Lord, I thank you. I’m not going to be fearful or scared of anyone out here, as you are with me.”