Houston, we have a problem.

Those famous, often misquoted words are emblematic of Houston’s identity as the home and heart of human attempts to explore the far reaches of space as early as the Apollo 13 mission.

Such is the prominence of the city in the space industry that UH has become home to a one-of-its-kind program and many other research projects dedicated to solving the problems of spaceflight before they reach the desks at Mission Control.

“It’s a good challenge,” said NASA Human Factors Engineer Yaritza Bernal. “We need something new to keep the public faith alive.”

Bernal entered the space research arena through NASA’s Career Exploration Program in high school, and that co-op internship allowed her to combine her interests in medicine and space.

Now an industrial engineering masters student, Bernal said she always wanted to help people in addition to being an astronaut as a kid, so she went into the medical field and graduated from UH with a biomedical engineering degree in 2017.

Instead of going into space herself, Bernal studies how astronauts’ bodies react to being in space. She works at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in the anthropometry and biomechanics laboratory, which focuses on the human body’s movement, its measurements, proportions and, as it relates to space, what happens to the body in microgravity.

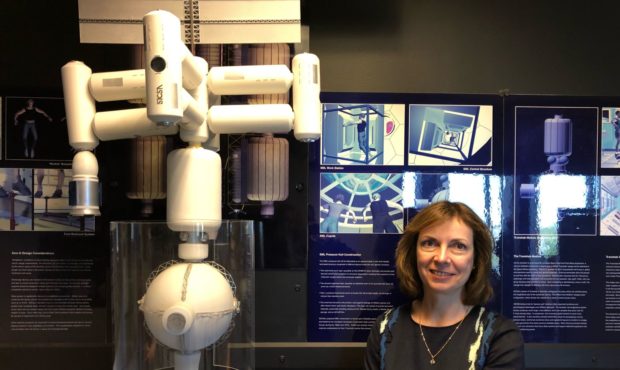

From a young age, Yaritza Bernal always wanted to explore the field of space. Now as a graduate student at UH and a human factors engineer at NASA, her dreams are becoming reality. | Courtesy of Yaritza Bernal

“It’s a neat experience to be able to do and help with the space program; especially the people,” Bernal said. “I’ve learned a lot of things on the job, but UH definitely gave me the background I needed to get started.”

Through her work in anthropometry, Bernal and her team perform 3-D scans of astronauts—she has worked with more than 50—after they return from space and observe how their bodies differ from pre-flight scans.

She studies how the human body operates inside a spacesuit, which is more intimate job than just engineering a suit, which mostly focuses on functionality, not ergonomics, she said.

Bernal’s team at JSC consists of eight people, and they can work on up to four projects at a time, she said. She’s working on analyzing the data from an underwater motion capture study and another project involving how people in spacesuits respond to microgravity.

The Space Architecture program at UH and its director, Olga Bannova, challenge students to envision a foundation for solutions to problems once considered far off but are now just over the horizon. | Drew Jones/The Cougar

One-of-a-kind

Olga Bannova, director of the Space Architecture program at the Sasakawa International Center for Space Architecture at UH, said students who enter are given the freedom to choose the projects that align with their passions.

In recent years, SICSA projects varied from designing a single-person spacecraft to a Martian orbiter to a three-person spacecraft intended to travel to and collect samples from Mars’ moons.

SICSA is working closely on projects for NASA, private contractors and European and Russian space agencies like the Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway, an orbiting station designed to facilitate transport to Mars and farther deep-space locations.

Space architecture students are encouraged to focus on all aspects of a space-related challenge, Bannova said. Whether it’s using limited resources, designing a habitable space, building an upper stage launch vehicle or 3-D printing materials, they do it all.

To achieve extensive manned space travel, engineers, scientists and students in programs like SICSA will need to solve issues like protecting people and equipment from cosmic radiation, how to recycle water on long journeys, sustaining air quality and producing food mid-trip that can support life, Bannova said.

She believes commercial spaceflight will play an important role in the coming years by taking on some of the responsibilities that have thus far belonged solely to the public sector.

“I hope that there will be more commercial presence,” Bannova said. “Because that would make it more sustainable (for everyone).”

Atlantis leaves the Hubble Space Telescope in its rearview during the waning years of the space shuttle program. Now, human spaceflight is poised to reach parts of the cosmos that have thus far only been seen in telescopic images. | Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

‘Space city’

Human spaceflight research is what drew David Temple to UH. He’s a doctoral candidate and teaching assistant in the Health and Human Performance department.

“Being in Houston, you’re in Space City, so there’s a lot of opportunities,” Temple said.

After coming to UH in 2011, he spent the summer of 2014 in JSC’s Space Life Sciences Summer Institute.

Temple has worked with Health and Human Performance assistant professor Beom-Chan Lee and professor Charles Layne on the “effects of tibialis anterior vibration on postural control when exposed to support surface translations,” according to the Somatosensory and Motor Research report.

The new direction with which private companies are heading is incredible to see, Temple said, and he believes there’s exciting new potential for human spaceflight research.

He knows firsthand what it’s like to envision new opportunities.

As a child, he wanted to become an astronaut but discovered in his adolescence he was colorblind, which would prevent him from passing a NASA-required physical.

Private companies could open up more people to the experience of spaceflight with different rules or regulations, Temple said, and he still hopes to one day sail beyond the atmosphere.

Lauren Gulley Cox, another doctoral candidate and research assistant in Health and Human Performance, received an undergraduate degree in aerospace engineering from Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Daytona Beach, Florida.

Her end goal was always to come to Houston.

She was always most interested in the human aspect of space travel, and after an internship at the neuroscience laboratory at Johnson Space Center, she hopes to work at the agency researching astronauts’ health in the future.

“I would love to be a researcher,” Cox said. “Making sure the astronauts have sensory motor health or exercise. I would be happy to help in any aspect (of space life science).”

“Being in Houston, you’re in Space City, so there’s a lot of opportunities.” — David Temple, UH Health and Human Performance

Newcomers enter the field

Now, zealous private companies like Elon Musk’s SpaceX are leaping into spaceflight and taking over responsibilities like resupplying the International Space Station.

SpaceX is laser-focused on building faster, higher-powered rockets, which is propelling the future of deep-space travel toward a bold new horizon.

Bannova, who directs UH’s space architecture program, views the private-public balance mostly as a collaboration. She wants students to focus on their projects through the lens of teamwork.

She challenges them to expand and adapt their work to include people from different backgrounds who perform different activities, like biologists or chemists, because private companies could introduce specialists who are non-astronauts to space missions, she said.

Bernal, the UH alumna, believes the private-public balance is necessary because of the issues NASA has faced moving cargo since retiring the space program. She said she’s proud of the fact that the company leading the charge into space is U.S.-based.

But who really holds jurisdiction in space and issues surrounding national security could make the proper balance between private companies and government agencies confusing, Cox said. She believes SpaceX and NASA should be required to work together and develop common standards for the projects they team up on.

Temple believes newcomer companies should respect the experience of an agency like NASA.

Temple and Cox agreed on safety being the top priority in future missions, and both said caution should be taken to ensure expediency doesn’t take precedence over proper standards and procedures.

“The last thing you’d want would be to have an inexperienced or not-as-well trained astronaut going up there and causing a big problem,” Cox said.

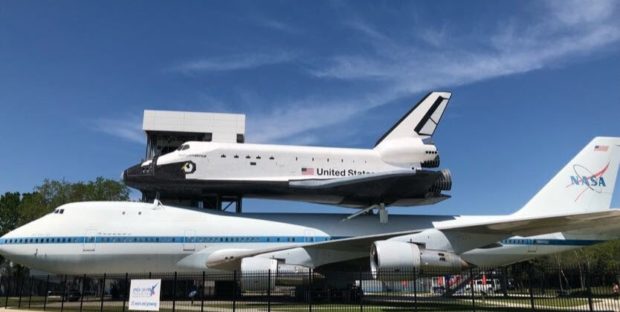

(top): Until the successful tests of SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy, the Saturn V, which was used in the Apollo missions, was the most powerful rocket in the world. (bottom): Johnson Space Center’s Rocket Park is the final resting place of many of its most powerful launch vehicles. | Drew Jones/The Cougar

Knowing the risks

Still, researchers across the world are concerned with the longevity of space missions into the far reaches of the solar system and the effects of prolonged travel on the human body.

“There’s still a lot we don’t even know,” Temple said. Information is still lacking about the harmful effects of radiation in space and the risk factors of sensory motor deprivation, bone deterioration and mental stress, he said.

While our understanding of microgravity is ever-increasing, nearly all of its effects on humans are negative, Temple said. One example: Astronauts who have returned from even six-month missions on the ISS don’t adapt quickly to functioning normally, he said.

That’s before considering how to logistically get astronauts back to full health on a mission to Mars, he said, which has one-third the surface gravity of Earth and, by most estimates, would take three years.

Researchers need to consider the psychological health of astronauts because different types of people don’t always mix well, especially in the confined environment of spacecraft, Cox said.

Scott Kelly, an astronaut who notably volunteered to spend an entire year aboard the ISS for research and observational purposes, showed that being isolated from people on Earth takes more than just a physical toll, she said.

In the words of Kelly himself, “a year is a long time to live without the human contact of loved ones, fresh air and gravity, to name a few.”

Charles Layne has seen the space industry grow over time, and his hope is that private companies take on human spaceflight while agencies like NASA pursue deep-space exploration. | Drew Jones/The Cougar

Striking a balance

Some observers believe heading into the future of space, the private and public spheres should split their focuses and delve into the areas with which they are most comfortable.

“You could argue that Elon (Musk) and other companies should worry about Mars, and let NASA get out of human spaceflight altogether and just do universe exploration,” Layne said.

As federal administrations shift rapidly from one priority to another, the balance between NASA and the private sphere has been difficult to maintain, he said.

Layne worked at NASA in the Space Life Sciences Program during the late ’90s studying interactions between living organisms and characteristics of the space environment. He remembers when President George H.W. Bush said he wanted the U.S. to go to Mars, while NASA employees wore buttons saying “Mars 2030.”

Layne believes SpaceX should take over developing larger, cheaper rockets, like the “world’s most powerful” Falcon Heavy rocket, because it will drive down the costs of hardware, allowing space agencies to focus on larger priorities.

“The hope is that if NASA can spend less money doing the basic things that private companies can do,” Layne said, “then there will be more money to devote toward better telescopes, or better preparation to go into deep space.”

But all wouldn’t be solved by handing the reins of space travel over to the Tesla-driving, “Space Oddity”-loving CEOs of the world, Layne said.

On the other hand, Bernal believes that expertise should play a major factor in who sends out the next manned trip, so NASA should handle manned crews and private entities could handle shuttles and cargo.

The space shuttle program developed six orbital spacecraft over its 30-year history: Atlantis, Challenger and Columbia (both destroyed), Discovery, Endeavour and Enterprise. | Drew Jones/The Cougar

A new era

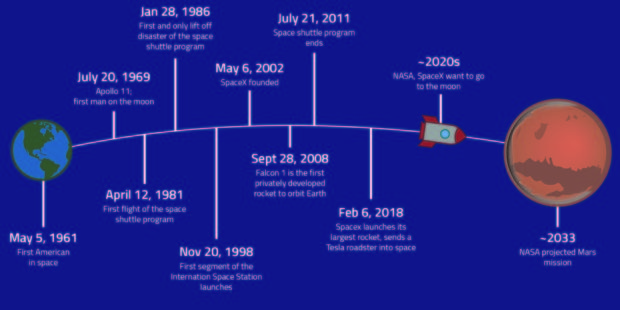

Thirty-seven years ago on April 12, the Space Shuttle program at NASA began as a triumph with the maiden voyage of Columbia.

Over the course of its 30-year history sending people and cargo into low-Earth orbit, 135 missions were flown by the Space Transportation System, yet it endured two major tragedies — Challenger exploded upon takeoff and Columbia disintegrated during reentry.

The accidents killed 14 astronauts.

While disasters are inevitable given the power and dynamics of rockets, the success rates are surprisingly high given the low number of mission-ending malfunctions, Layne said.

Agencies and companies are entering uncharted territory because there’s never been an alternative to manned missions piloted by NASA, he said, so it could become difficult to assign blame.

“If SpaceX (was at fault), people would say, ‘Oh, (the astronaut) knew the risk,’ but if NASA (was at fault), then there would be a crisis,” Layne said.

NASA is currently developing the Orion spacecraft, which is expected to take humans farther than any mission has gone and will begin testing later this year. Orion will feature “crew and service modules, a spacecraft adapter and a revolutionary launch abort system that will significantly increase crew safety,” according to the agency.

SpaceX’s current directive, at the behest of its founder, is to complete a cargo mission to Mars aboard the reusable BFR rocket by 2022 and send a crew to the red planet by 2024. Beyond 2030, Musk wants humanity to “become a space-bearing civilization and a multi-planetary species,” meaning naturally inhabit more planets than just Earth.

NASA’s efforts, as outlined by its 2018 Strategic Plan, revolve around four strategic goals: expanding human knowledge through new scientific discoveries, extending human presence deeper into space and to the moon for sustainable long-term exploration, addressing national challenges and catalyzing economic growth and optimizing operational capabilities.

Outside of potential disasters, Layne said radiation and crew housing are significant limiting factors in spaceflight.

Layne has also contributed to research on programs like Mars in a Box, which is a UH collaboration with NASA designed to improve and maintain astronauts’ sensorimotor function during space missions.

UH has a significant advantage in having NASA “in its backyard,” Layne said, because of the valuable face-to-face interactions students are able to receive from the agency’s scientists.

Inside SICSA, graduate students are earning masters of science degrees in the world’s only space architecture program. They are leaning to identify and solve the problems of the future of space travel. | Drew Jones/The Cougar

SICSA, celebrating its 30th anniversary this year, started as the dream of space startup founders James Calaway, Guillermo Trotti and Larry Bell. Bell, who started at UH in 1978, helmed the program for nearly its entire history until stepping down last year, leading to the appointment of Bannova.

With the help of a Japanese benefactor, Bell and UH received the endowment to begin the program, which in 2003 became the only program in the world to offer a master of science degree in space architecture.

Students come to UH and the space architecture program because of its proximity to Johnson Space Center and for the expertise and inspiration they receive from NASA professionals who are excited to share their work, Bannova said.

“When you meet people who are really devoted to what they’re working on, and excited and motivated, it’s wonderful,” she said.

Accepting the challenge

Due to budget cuts and the difficulty present in funding programs NASA wants to pursue, collaboration with the commercial space industry is a positive sharing experience, Bernal said.

Regulations have become stricter, she said, but private companies like SpaceX should take on NASA’s “we’ve done it before” attitude.

She considers Kelly’s time in space to be NASA’s highest achievement of the past few years. It was also an endeavor to see how long he could stay in space based on what was happening to his body.

Her work remains challenging because no two people are alike when it comes to test results, she said, and the impact of spaceflight on the body can vary widely based on the duration of the mission, the health of the astronaut and how accustomed they are to being in space.

She plans to go further into the realm of her research, which she truly enjoys, she said. She values being able to come to UH with the goal of becoming more well-rounded by gaining a valuable engineering background to complement her work with the human body.

While NASA is under intense scrutiny because of its sky-high profile, a manned mission to Mars is “definitely” possible by the end of the next decade, she said, and hopes SpaceX will follow suit in chasing humanity’s dreams into the final frontier.

features@thedailycougar.com

The U.S. has played a major role in sending humanity into space and will need the ambitions of private companies and research universities to go farther into the final frontier. | Sonny Singh/The Cougar

—

“Space City, UH look to lead future of spaceflight research” was originally posted on The Daily Cougar