Vivre Sa Vie (1962)

Jean-Luc Godard’s 1962 landmark drama Vivre Sa Vie features his then-wife and muse Anna Karina as Nana, an aspiring actress forced into sex work to make ends meet. Borne from non-fiction reports of Parisian sex workers, Godard handles this controversial issue with refinement, utilizing his trademark avant-garde style to craft a universally affecting character study.

Godard exposes the inherent artifice of cinema through his insertion of intertitles that tell the audience what’s going to happen, as well as compositions and camera movements that jolt the audience from passive spectators to engaged participants. Consider the opening scene, which depicts a conversation between Nana and an ex-lover in a café: in a far cry from the emotional omnipotence of the audience in classic cinema, the characters’ backs are towards the camera, seemingly aware of the fourth wall and purposefully shutting the audience out. Only through concentration and involved viewing will we be able to decipher Nana’s inner personality, since Godard doesn’t present any obvious denotation of her emotions.

In the opening scene, the characters’ faces can be seen only fleetingly in a mirror, acting laconic and detached — perhaps Nana’s two defining characteristics. She, fittingly, is far away from the mirror, just like the camera. Distance suggests obscurity — she is unable to look at herself up close, to gauge her true desires or inner purpose. The world doesn’t provide any answers, either. She’s too thoughtful for the boring record store where she previously worked, and everyone around her seems cruel and indifferent. In a rare instance of emotional vulnerability, Nana cries while watching Joan of Arc succumb to the external forces around her in The Passion of Joan of Arc by Dreyer. Yet she remains determined to find her destiny. She disavows fatalism when she proclaims, “I raise my arm — I’m responsible. I turn my head — I’m responsible. I forget I’m responsible but I am.” In other words, nothing arises from the follies of the universe. Our actions make up our experiences and because our actions stem from our free will, we are responsible for the trajectory of our lives.

But then comes the inevitable query: why is Nana so detached? If her destiny is dependent on her actions, shouldn’t she act in a manner that’s not so cold? The answer subsequently becomes the quasi-thesis of the film, summed up by a philosopher in a café: “To live in speech, one must pass through the death of life without speech.” In other words, to appreciate and understand life in a fulfilling manner we must temporarily withdraw from it. Nana’s cold demeanor is a necessary transitional state for eventual enlightenment, and it pays off. She meets a boy in a dive bar and starts dancing with him, experiencing a newfound sense of joy. They become infatuated with each other, sharing lazy afternoons reading short stories aloud and wondering what pointless activities they can do. They ultimately embrace by a window that is completely filled with bright sunlight, adding a rare aura of warmth.

The joy is short-lived, however. Simultaneously with Nana’s spiritual growth, Godard presents a tragic path illustrating what he perceives as the dehumanizing nature of sex work. A montage commences of Nana with various clients; Godard frames a different part of her body after showing an exchange of cash, symbolizing her commodification. He then shows an anonymous hand rubbing her body, representing the appropriation of Nana — a living person — by a nameless, paying figure. The most poignant example of Godard’s stylistics occurs in the first one-on-one meeting between Nana and her future pimp. During their conversation, the camera is situated right behind the man, his head blocking hers from sight, for two-and-a-half minutes. The camera moves in vain to try and recapture Nana’s identity; when the audience glimpses her face, it is framed in between the man’s head and her letter of intent to begin selling sex. Godard has Nana become defined and ultimately controlled by her faceless clientele and her emotionless pimp. In the last scene, she is reduced literally to mere currency by her pimp despite her inner growth as a person. It ends tragically, a sickening reversal of the earlier hints of joy.

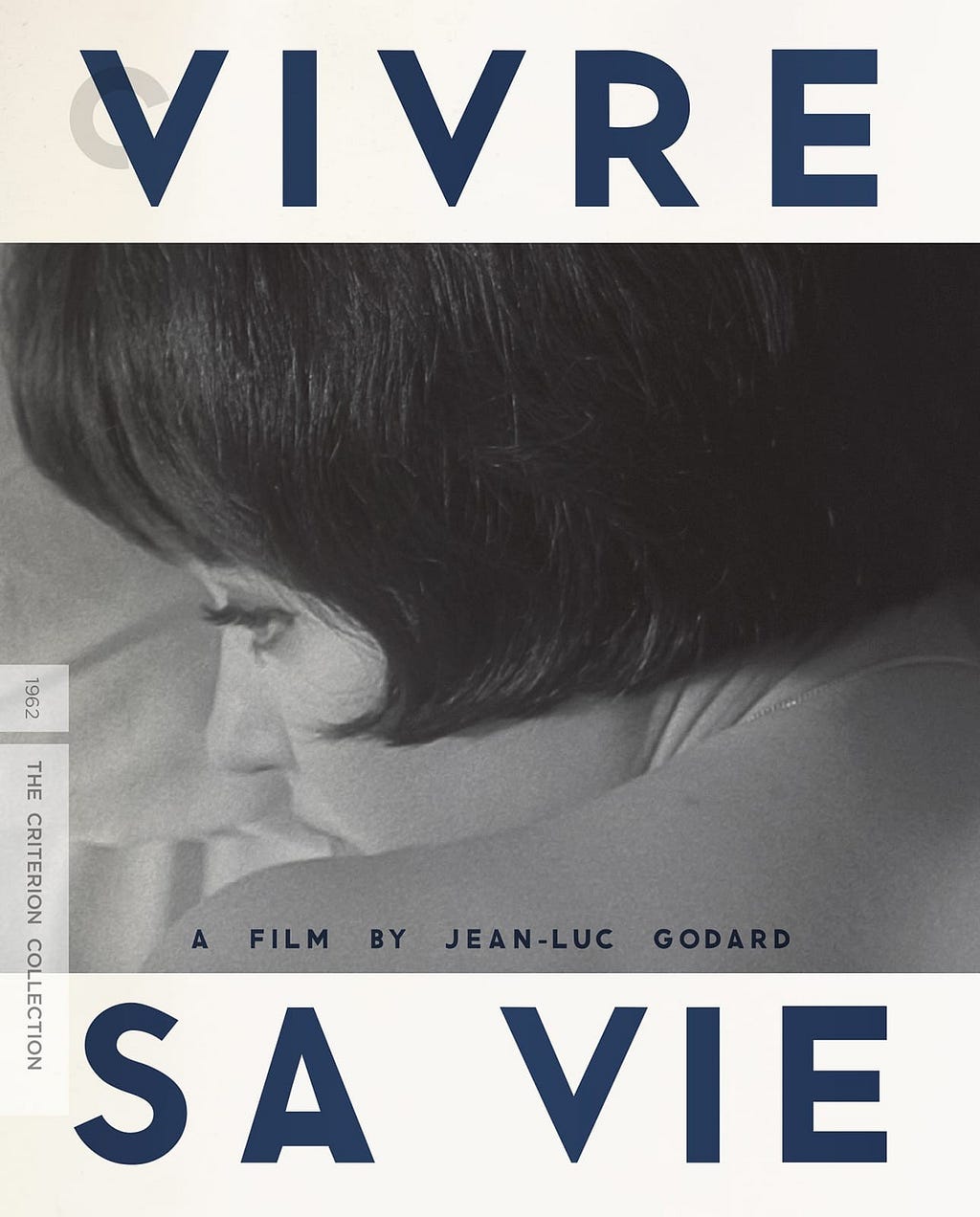

Brimming with avant-garde self-reflexivity, Vivre Sa Vie has become a cornerstone of cinematic modernism. It wears its influences on its sleeves, something unheard of at the time but has since become commonplace. In one scene, Nana watches the silent classic The Passion of Joan of Arc and identifies with the titular martyr; in another scene, Godard co-opts the silent aesthetic and uses subtitles for dialogue. Nana’s hairstyle was based on Louise Brooks’s bob in G.W. Pabst’s 1929 classic Pandora’s Box.

Vivre Sa Vie is an emotional gut-punch of a film. It may not be ideal for a romantic night in, but for a revolutionary and powerful character study, Vivre Sa Vie remains unsurpassed.

Vivre Sa Vie was originally published in The Yale Herald on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.