This week, the Herald talked to painting student Krysal DiFronzo, ART ’20, about how she navigates her process, research, and imagery.

Yale Herald: When we spoke earlier you pretty readily identified the occult as a key theme in your work. I also know that before coming to Yale you published a comic about your experiences as a young cancer patient. To start us off, I was wondering if you could share a bit about how you see those two sources of content relating to one another?

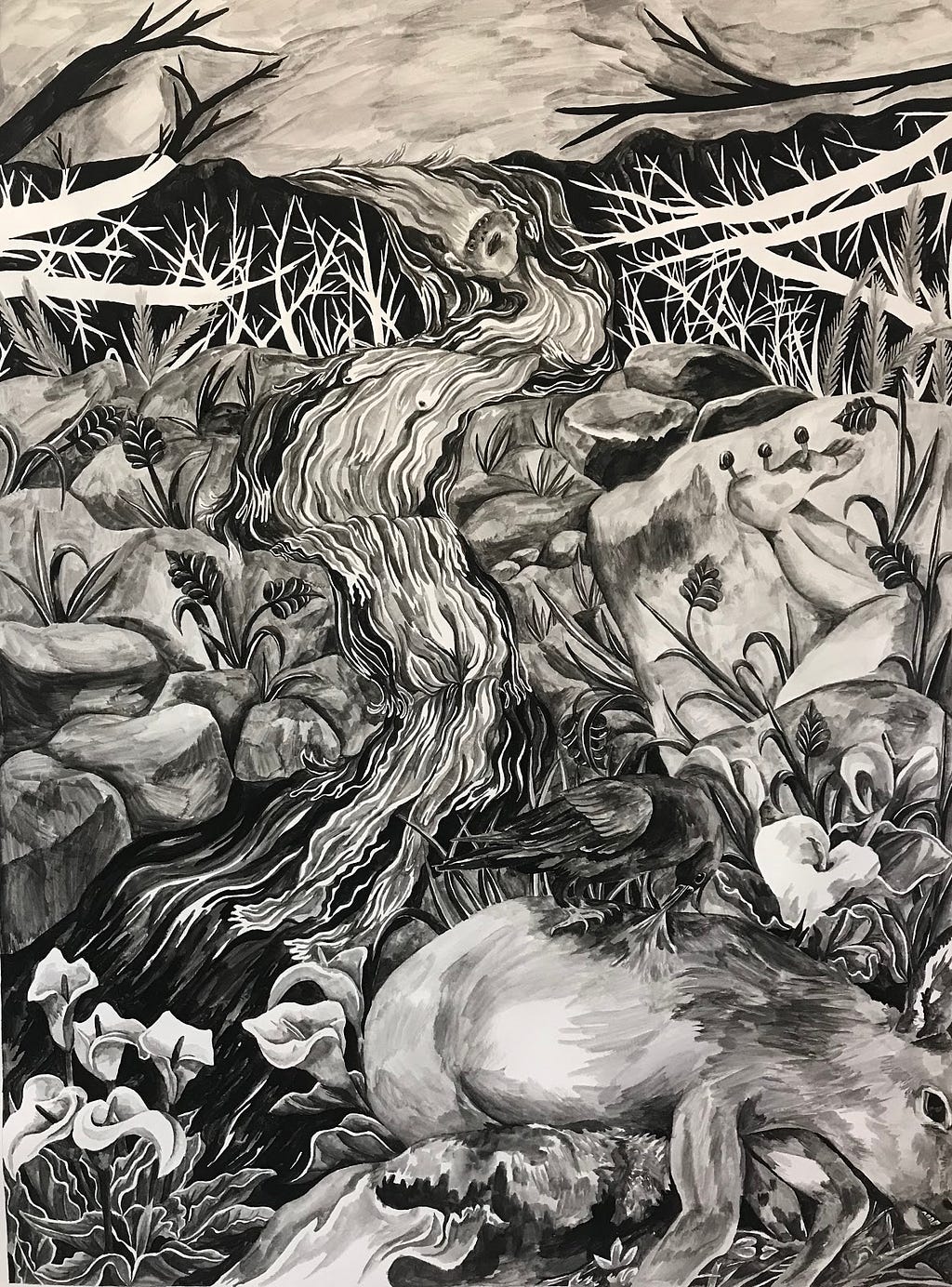

Krystal DiFronzo: Right now, I’m being a lot more explicit about going back to my experiences with chemotherapy and treatment, thinking about moments when boundaries of the body and the environment get broken down. With superstition, I think a lot about the relationship of illness to psychosis and hysteria in history. When I first came here, I was doing a lot of work researching histories of possession in relation to mental and physical illness. Susan Sontag has a great quote where she talks about tumors as demonic pregnancies. I’m interested in looking at sickness in this way — the body growing out of control, without the ability to resolve itself. What does it mean to have or to be this thing that’s of you and not at the same time, taking over your bodily control and health?

YH: Do you believe in “irrational” practices as meaningful to your personal life outside of the work?

KDF: When I first moved to New Haven, I lived in this apartment which I thought — and I’ve never had this experience before — was truly haunted. Like truly, completely haunted. I grew up in Chicago. It’s not a young city, but it’s not as old as here. The apartment had the worst energy I’ve ever experienced. I didn’t hear noises or anything, you know, other than the sounds from the heater, but it just had a bad vibe. I guess I do kind of believe in energies. It’s kinda woo-woo [laughs]. In my work, maybe it manifests in the transparency of the paintings on silk. I’ve been looking at a lot of spiritualist-era photography of people performing seances and producing ectoplasm. In these photos, the photographer tried to capture this moment: both to show it happening, and to debunk it. That liminal space of the photo is important to me, how it relates to the ghostly, the superstitious. It’s like alchemy, you know, chemicals and light becoming image.

YH: There’s a kind of irony in that — to preserve the mystical while also maintaining your own sense of “rationality” or scientific logic. It’s interesting to hear you laugh as you describe the energies in your apartment; a kind of necessary contradiction at play in the representation of magic or so called “other-worldliness,” something which the photograph symbolizes so clearly. Representation, at least as we think of it today, can’t really be separated from the technological. Do you think of these paintings as sincere identifications with a mystical way of thinking, as trying to break that scientific logic of meaning?

KDF: They’re mostly sincere. I’m a strong believer that women have been placed as witches because of their relationship with death, healing, and birth, their ability to create healing substances that can also be poisonous. I like the idea of this feared status. Though still I’m unsure where I lie on that spectrum of ironic distance. If the work is reclaiming an identity, a way of thinking, it’s definitely complicated to do so within this specific historical frame. I do link myself strongly to that history, but in the end I’m not sure of the extent that the work can do the same.

YH: You talked about a kind of dominion over the natural and this power to convert nature into something that can be healing or harming. There’s an obvious relationship between that kind of conversion and what you’ve been working on materially — using these natural dyes and these complex pseudo-alchemical processes. I guess they’re actually just kind of chemical [laughs]. But I’m wondering how the metaphor of material translates into the image, the movement between them.

KDF: The chemical has a similarly ironic relation to the occult, to the alchemical. There are places where the historical evolution of drug-therapy has hinged on the apparently sinister. Obviously some Western medicine is also a poison. I’ve been thinking a lot about chemotherapy drugs — the way in which a poison can become medically beneficial. Looking into the histories of these drugs and figuring out the origins, I could clearly see that some had been derived from the production of mustard gas, [and] other highly toxic, weaponized substances. Almost all of these things are derived from natural sources, different types of molds and plants — it’s almost as if the scientific interest in these sources relied on a leap of faith, a superstitious interest in paradoxical effects, to make them into something beneficial. The metaphor here I take to be integral to my work — the way in which dyes become image, the natural supplanted into the realm of the delirious or the occult.

Artist’s Portrait: Krystal DiFronzo was originally published in The Yale Herald on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.